American Chicano and the Path To ‘Insurrection’

It was January 6th, 2021 and J.D. Rivera, AKA: “The Chicano Patriot”, had every reason to be excited. After a lifetime of sacrifice, dedication, and hard work, it seemed as though fate had just smiled on the burgeoning freelance journalist and filmmaker.

Just one month earlier, Rivera had parlayed his prior experience into getting an interview with WKRG’s Chief Photographer, Jason Garcia. The paperwork was all filled out and he was encouraged to bring back footage from the Trump Rally on January 6th. He never imagined how historical his footage would become, but as he documented the chaos at the Capitol that day, he was sure that his position with WKRG was secured. “I'm thinking, if I get this footage —wherever I get it, this is probably going to help me get this job,” Rivera explained in an interview on June 3rd of this year. “So the entire time I'm feeling like this is going to spark my career. This is what's going to take me to the top.” Little did he know that just two weeks later he would be placed in handcuffs and leg irons, taken from his family, and facing four federal charges.

Like many who were in Washington, DC that day, the story of how he came to be there remains woefully underreported and stands in stark contradiction to the lies of the mainstream media narrative. His story begins with his birth in Yuba City, California, in 1984.

J.D. sits on his mother’s lap as his brothers and sisters join them for a photo

His mother, Yolanda, was born in Texas. She already had four children before meeting his biological father, Jesus Delamore Rivera Sr., who was born in Tijuana, Mexico. Rivera says much of his early childhood is unclear and could easily be described as being somewhat tumultuous. While J.D. was still in the womb, his mother left his biological father because he had apparently relapsed into drug addiction. “I was her final kid that she was going to have, so she wanted to do life right,” Rivera explains, “and she literally just up and left. She took us and just walked away because she didn't want us doing drugs. So it was kind of one of those things where he picked drugs over a family, and that's literally all I know of my biological father from that time. I don't even know if I have a picture of me as a baby with him or not.”

Shortly thereafter, his mother met the man who would become J.D.’s first stepfather, and the family moved to Massachusetts. Unfortunately, that situation turned out to be anything but perfect, and much like the rest of his first few years, memories are less than specific. “I just do know that my original stepfather was a complete douchebag,” he says. “He used to beat the hell out of my mom, and I do remember those things. I was a kid, but I remember being on buses. I remember we traveled from Massachusetts to California and then my grandma told me about what was going on with my mom at that time, but I don't remember a lot until I was about six, seven years old, when my new stepfather came into our life. And that's kinda where all of my memories start picking up from there.”

J.D. describes the next few years as “a very typical Mexican story”, with his mother working several jobs and his new stepfather, Joe, also a Mexican immigrant, working in the fields. It was very common for him to be rousted out of bed at 4AM to go out and help pick peaches, but outside the bounds of work, he doesn’t recall much of a relationship with his stepfather. “I didn't really have a father,” he explains. “Now mind you, he was my stepfather, but I really didn’t have anyone there for me growing up to call on or ask questions. It was always just ‘you're-working-or-you're-in-trouble’ kind of thing.” He would finally meet his biological father at the age of 11, but just a short year later — long before that relationship had a chance to blossom, Jesus Rivera Sr. passed away.

Without a real father to guide him, J.D.’s relationship with his mother was essential. He focused on sports and school, and excelled at both. As he reached his 18th birthday, he wrestled with typical questions about what to do next. “I didn't want to go to college. I didn't want to stay in my hometown, but at the same time I did cause I was still immature,” he recalls. “I picked up a job with my mom working at Hewlett Packard, and I was doing line work, and I was like, ‘This is not my life, this is is not what I want to do,’ and I remembered that I had talked to a Marine recruiter earlier that year, and I was just like, ‘I'm gonna go talk to him again’.”

J.D. celebrates his 18th birthday with his nieces and nephews.

Unbeknownst to his mother or anyone else in his family, he met with the recruiter and took the ASVAB. Before anyone could question his decision, he had gone through MEPS and a date was scheduled for him to report to boot camp. With all the official business handled, J.D. told his recruiter that he was going to have to go home with him to tell his mother what he just did: “So, sure enough, we go home and my mom's looking at me and she's pissed as she’s sitting on the couch, and my dad is standing up and they’re just pissed.” His recruiter explained that J.D. had decided to join the Marine Corps and he would be shipping out for boot camp in December of that year. At that moment, his mother wasn’t happy, and any sliver of relationship he had with his stepfather was gone. “When I joined the Marine Corps, he completely just shunned me,” J.D. says. “He was just like, ‘I'm done with this kid,’ and I was like, ‘okay, whatever’.”

With his childhood almost completely behind him, J.D. says he spent the rest of the summer “acting like a fool and being stupid”. He received a call in late August and was told that his date had been moved up. On September 12th, 2002, he reported to boot camp at the Marine Corp Recruitment Depot in San Diego.

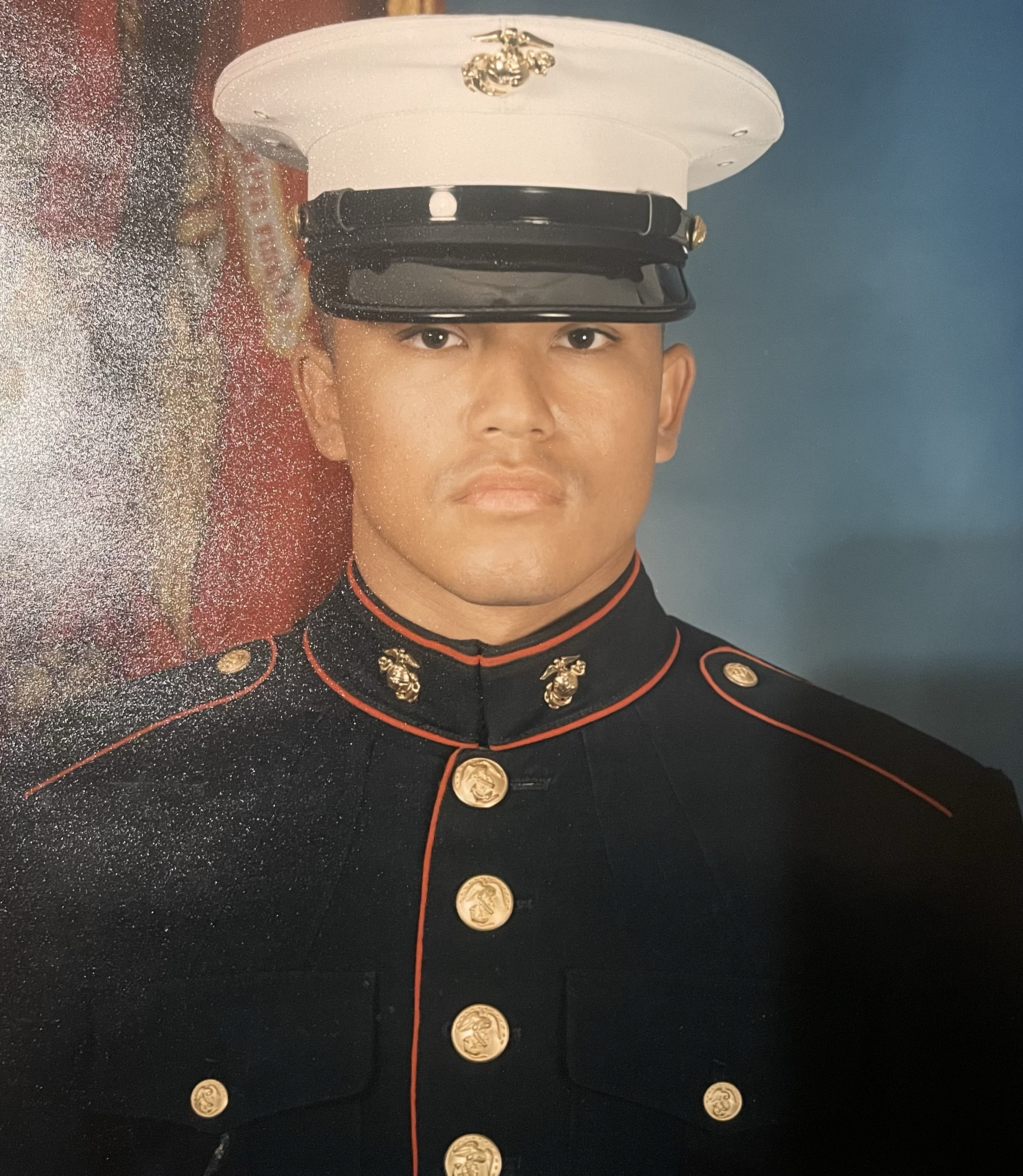

“I still had no idea what I had gotten myself into,” J.D. explains. “I went in weighing 215 lbs, and had full grown facial hair. I was a typical high school kid that doesn't care about life. When I came out I weighed 165 and was clean-shaven. It was three months of hell, but it was a good time. I mean, obviously I learned a lot about being a man.” It wasn’t until after his graduation that the gravity of his decision began to dawn on him; He was imbued with a level of patriotism unlike anything he’d felt before, and his pride was at an all-time high. “After graduating, realizing what I had done and what I become, it was pretty rewarding at that point,” he says. “Not only did I just graduate from high school, the first in my generation, I'm the first one in my family to ever join the service.” After not knowing what he was going to do with his life less than one year before, Private Jesus Delamore Rivera Jr. was a United States Marine and he was ready to take on the world.

United States Marine Corps Bootcamp Photo

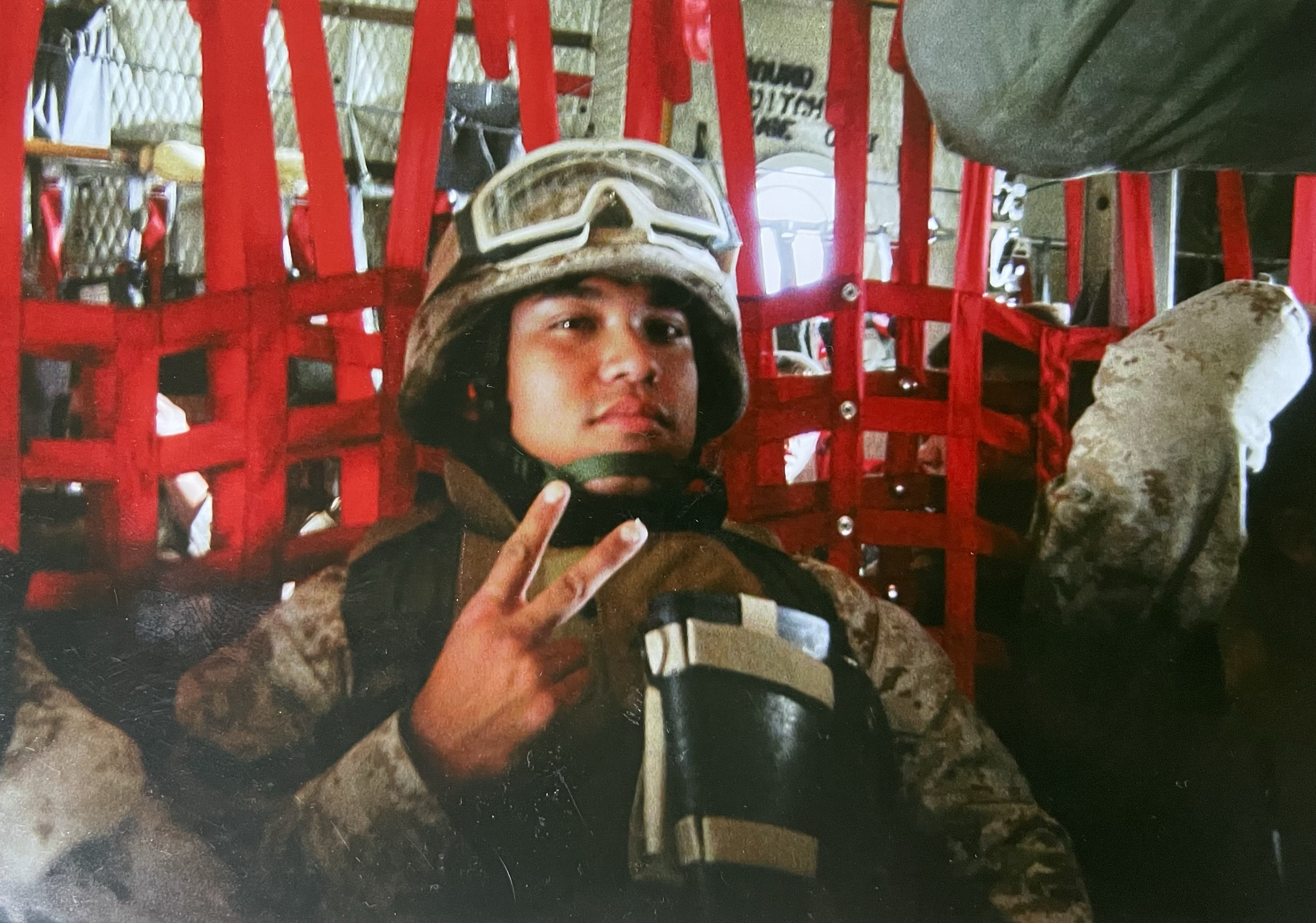

In 2003 he was shipped to Okinawa, Japan and looks back on that experience as being the best time of his life in the Marine Corps. “I was 19 years old, in a foreign country, and it was just amazing,” he recalls. “Being able to see a different life than what I was used to seeing in California and some parts of Mexico, it helped me understand how different things are in different parts of the world.” Over the course of the next year he fell into a routine in the supply side of the Corps. He says it was like working at the Lowe’s or Home Depot of the Marines with an NCO structure that kept the entire base running smoothly. In March 2004, he returned to the US where he was informed he would be getting shipped to Iraq. His assumption was that he would still be working in supply: “I'm sitting there thinking that I'm just going to be a supply guy and sure enough, that was a no. They said ‘You’re getting augmented from supply to First Marine Division and you're going to be heading out’.

J.D. participates in jungle warfare training exercises as a radio operator in Okinawa.

As insane as it seemed to him, he was ready to do his job. When he arrived in Iraq, he was immediately given a station, maintaining a supply house in Ramadi, made out of 2x4s and plywood. “It was at one of Saddam's old palaces that we took over,” he explains, “It was a castle really, even the fortification around it. That’s where we had a tower so we can post up to see what was going on out in town, outside of our little areas.” It wasn’t long before J.D. gained an acute understanding of why the Marines had trained him as a rifleman. “That’s when all the craziness happened. And, you know, I learned real quick that being a rifleman first is important,” he explains, “and when I was getting into it, I was happy to know how to shoot my rifle and what needed to be done in certain situations.”

“Certain situations” included being stranded with a broke down Humvee, “somewhere in the middle of nowhere”, between Ramadi and Kuwait. “We left Kuwait and I don't know where we were at this point, because we had driven for two or three hours,” he says, “we were already on the road when the Humvee broke down, but and we were stuck there, and things took a pretty bad turn, but you know, obviously we came out okay.” Six days later, J.D. and those with him were discovered by accident, by a north-bound Army unit; a situation that he says is all too commonplace: “These stories of people being stranded or being left behind happen way more often than people realize or want to think about.” When J.D. says “pretty bad turn” he declines to speak publicly about what exactly transpired, but he reiterates the reality that there were multiple occasions where he was uncertain as to whether or not he would make it out of the war alive. “There was lot of stuff that happened in Iraq,” he says. “It’s amazing that I'm actually here today, being able to tell the story.”

As many who’ve served can attest to, coming back to the “regular world” was no easy task. “I got back in March of 2005, and it took me a while to get used to it,” he explains. “Everything that I drove by was an IED. Every loud sound was like I was caught in a rocket attack or a mortar, or getting shot at. I couldn't be around large groups of people because everybody was suspect to me and everybody looked like potential problems for me...I was still just a kid. I had just turned 21, and I was trying to figure out how to be normal again.” Desperate to return to the trauma of war that he had become conditioned to, J.D. attempted to get shipped to Afghanistan. “I requested to go and I got denied because I was in a new job field, back in San Diego where I started, and I was in charge of the drill instructors’ gear and took care of all their uniforms or whatever,” he explains in a disappointed tone. “So it went from a very crazy atmosphere to a very civilianized [sic] atmosphere, so that wasn't all that good for my mental health, but that’s how it goes.”

J.D. on his way to Al Asad Airbase in Iraq.

As he attempted to move forward with the Marines, he was given two options: One was to become a recruiter, and the other was to become a drill instructor. He applied to become a drill instructor but was quickly reminded of how his time in the Marines was consistently marked with never getting his choice. He was given orders to become a recruiter, fresh out of Sergeant’s School at 29 Palms. When he asked to stay in San Diego, his commanding officers sent him to Montgomery, Alabama. “I'm like, what the hell? Like, what is a Hispanic Marine going to do in the Montgomery, Alabama?”, Rivera says.

After a month and a half of trying to sort through the inevitable challenges of being a Hispanic recruiter in a Black community, the Marines asked him if he wanted to go to Pensacola. He quickly agreed, but even after transferring to a place where he should’ve experienced success, J.D. continued to struggle. “It was a really horrible time as a recruiter because I was going through a very crappy marital life at that time,” he explains: “There’s a lot of it that goes into that. I'm not trying to bring her down this situation, but my wife left and I stayed back. I didn't get to see my kids and it was depression times a million.” It was 2011, and J.D. Rivera knew that being a recruiter wasn’t what he was meant to do. As his divorce became finalized, he met his future wife, Jessecah, and his time in the Marines came to an end on April 20, 2012.

Soon enough, Jessecah was pregnant with their first child, and J.D. knew he couldn’t keep spinning his wheels in Pensacola. After 8 years of being constantly told what to do, his path in life was completely up to him. At the behest of his oldest brother in New Mexico, he packed up and took the mother of his then-unborn child to The Land of Enchantment. He found employment as a fitness instructor and started going to school for a business degree. In late 2013, he discovered a new path when he was asked to be an extra in the movie “Shot-Caller”, that was being filmed in his area. “I got the bug dude,” he explains. “I wanted to be in movies, but not as an actor. I wanted to be a part of the production. I wanted to be the guy that makes it happen.”

J.D. and Jessecah with their first child. 2014

The opportunities were endless for J.D. as he developed relationships in the film community. He was cast for several more roles and began producing films with others he met in the process. There was no job in the business that was outside of what he was willing to do, and he made himself available for whatever might come his way. Things were going great as he worked to realize his dreams, and Jessecah had given birth to their second child. J.D. decided it would be best if he got a vasectomy because he was done with having children, but as he puts it: “God had other plans”. Shortly after the procedure, he and Jessecah discovered they would be having twins. With yet another child to care for, the need for steady employment with benefits became much more important. Once again, JD went to work for the federal government, but this time it was at a bottom of the line job as a phone operator for the Veterans Administration.

J.D. and Jessecah with an ultrasound of their twins.

Just when he thought things were under control, J.D. learned that his twins were experiencing Transfusion Syndrome; a rare condition where one twin steals all nutrients from the other. The complications were immensely stressful and were only exacerbated by a late pregnancy ultrasound where he and his wife were confronted with a terrifying possibility: “When that was happening at the appointment,” J.D. explains, “the doctor said, ‘the next time we do this, there probably won't be a heartbeat, so be prepared for that.’”

Confronted with the heartbreaking possibility that one of his sons could very-well die, he cried out to God. He prayed and made promises to change his life, or go to church more, or “stop doing this and that”. In these moments of fear, J.D. was desperate for a miracle and was begging God for intervention. Two months before her due-date, Jessecah was rushed to the hospital for an emergency C-section and J.D. was given the call to come join her at the hospital. When he arrived, what he saw was terrifying: “I've been to war and I've seen some horrible stuff, but one of the very worst things I ever encountered was walking into the room where my wife was being given the emergency C-section,” he explains. “I knew it was going on, but it was just a visual, like when you walk in and you see your loved one, who's on this bed and unable to move, and you just see someone cutting their skin open. It's like, it's a whole different scenario that goes through your head.”

Jessecah was losing massive amounts of blood, but the first of the twins had been delivered successfully. The second, however, was completely unresponsive. As the doctors and nurses worked frantically to save his life, J.D. was overcome by an nearly indescribable feeling of peace in the midst of the storm. “The whole time, I felt okay,” JD explains. “Like, in a situation like this, where my wife is bleeding out and one of my kids is lifeless, you would think that there'd be more emotions going on, but there wasn't. I really felt like God was right there with me the whole time and was moving me along to let me know everything was going to be okay. It was just a sense of calm; the most calm you could ever feel.”

Doctors urged him to go to another room to be with his first twin, and in a state of divinely inspired calm, he readily agreed. Just a short time later, a nurse walked in and asked J.D. if he was ready to meet his other son. Tears of joy began to fall. “I was so happy. He was okay,” he explains. “Even though at this moment, I didn't know that my wife was almost lifeless in her bed as they were trying to stop the bleeding.” Nevertheless, JD somehow knew everything was going to be ok, and that his wife would survive. “I knew God would take care of it,” he says. “I did tell him I would change my ways. It was just 100% and it really helped me understand where my relationship was with God was wrong, and where it needed to be. So that was a really cool transition from me being agnostic to a Christian.

The Rivera family after the birth of the twins.

Unfortunately, no paternity leave was available from his position at the VA, and he was let go due to his inability to prioritize the job over the needs of his family. Even though the twins were in the NICU for the next two months, and Jessecah continued to deal with complications from the trauma she had endured, J.D. says, “From there, things just got really good.” He was still going to college and he continued to find work in film production. After Jessicah’s recovery and the realization that his future would never be sitting in a cubicle and answering phone calls, the family made the decision to return to Pensacola in 2017.

Having devoted his life to Christ, J.D. became extremely active in the church where his wife had been raised, and soon found a way to utilize his passion in the furtherance of his faith. “I still really wanted to get into film, and I was trying to figure out film stuff in Florida,” he explains. “I was getting some odd gigs, working on crews on different reality TV show crews, and I was a camera operator for a family feud show at one point, and I was just stuck. So I asked my church if I could start doing camera work for them because I saw a need. So I started giving them my expertise from the cinematography world.” As 2017 gave way to 2018, JD was fully focused on positivity. Even though some people were screaming frantically about Donald Trump, politics was the last thing on his mind. In 2019, however, things took a different turn.

J.D. stands with Hellcat Productions in front of a photo he took at the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

“All this stuff started happening, with Biden coming in and everybody just blaming Trump for everything, and I started getting really big on social media,” he explains. “I had started on topics of faith, but I had a political post go viral. I had said something about me being Mexican. Someone went off at me and I said, first off, I'm conservative or I'm an American first and that blew up. And so I have these huge followings on Tik-Tok and Facebook, and all of these people are using me as a voice, and a Hispanic group named LEXIT picked me up.” LEXIT contacted J.D. and asked if he would be interested in doing production work for their organization and it immediately seemed like the right choice. He hit the road as a cinematographer with the “We the People Tour” and traveled across the United States throughout the summer. He was enjoying the job and looking forward to a future in the business of broadcasting. Things were going great until Biden seemingly won the election and the movement lost purpose. “So at that point, everybody was just like, ‘There's no point anymore’. So we left it at that and I went home.”

JD poses with Forgiato Blow next to “We the People” tour bus.

When J.D. returned to Pensacola, he was heartbroken to find that division had crept into the church he called home: “Now, we're talking about the big divide between people who openly support BLM and everybody else,” he explains. “And if you don't support BLM, then you're a racist.” The place where he’d found so much unity and strength just a few months earlier had become consumed by the very thing he’d been working so hard to prevent. Once again, he was left with a feeling of homelessness and a lack of purpose in his life.

Things changed when in late December 2020, he received a phone call and was asked to go to Washington, DC for a rally that was being planned on January 6th. J.D. told his wife that it would be their last opportunity to be part of the movement he’d devoted so much of his life to throughout the summer. He assumed it would be the last opportunity to hear Trump speak as President, and he was certain that the historic nature of the events he planned to capture would ensure his position as a photojournalist or camera operator with WKRG. What actually happened came as a complete surprise.

“On January 6th, we were up early,” J.D. says. “We were running around with my buddy, Craig Long, and I was essentially just documenting him.” MAGA rappers Topher and Bryson Gray were with J.D.’s posse as they attempted to move through the massive crowd that had assembled to hear President Trump speak. “We were so far back point, that we were just kind of in the crowd, in the moment. I didn't really care who was on stage until Trump came on and everyone got all excited,” he says. “So we stopped to listen to him a little bit and then everything stopped when he said, “We’re going to march down to the Capitol.’ So we did like everybody else and we started marching down to the Capitol.”

As they began marching east on Pennsylvania Avenue, their group was inundated with people wanting to meet them, making it impossible to move forward. As a result of their lack of progress, they all decided they would go find something to eat and catch up once the crowd had completely assembled on Capitol Hill. After sitting down at a table, the messages of mayhem began to roll in. “As we're eating, everyone's just like, “Yo, check this out, check this out. Look, what's going on at the Capitol, they're storming the Capitol. They're doing this.” J.D. explains, “People are calling us, texting us, messaging us, ‘where are you at?’”

After thirty minutes of nonstop messages, he turned to his wife Jessecah and explained that he needed to go, he needed to be in the action, “I told her, ‘I came to document whatever is going to happen. This is what I came here to do. We knew something was going to happen, but this is going to be different. Let’s get the footage we can get and we'll get out of there, but I'm going to kick myself in the butt if I don't go down there and get in and get this footage.” J.D. and Jessecah bid farewell to the rest of their group and made their way into the mayhem. They promised to be careful, and stay in constant contact.

When he and Jessecah arrived at the Capitol, it was obvious that the situation had gone to hell. He told his wife to stay back, but that he was going into the action. With his camera rolling, J.D. went directly into the fray. His footage captured varying degrees of both peace and violence; further testament to the nuanced nature of what actually happened that day. Much like his time as a US Marine, he went in voluntarily and he left voluntarily.

A screenshot of J.D.’s livestream from inside the Capitol on January 6th.

As he and Jessecah drove home to Pensacola, FLA, on January 7th, he messaged WKRG’s Chief Photographer, Jason Garcia, and it seemed as though his dreams were coming true: “I was just like, all right, we're heading back. He's like, ‘I saw everything. You got footage. We really want to talk to you, please call us back. We want to offer you this job. We want to get you on this team ASAP.’ I'm like, hell yeah, Right?”

On January 14, Rivera received an email from the station’s business administrator, Wendy Hancock. The subject line read “WKRG: Welcome Aboard!”, and the body explained that his start date would be January 18. Things were looking great for the Chicano Patriot, but his relationship with WKRG deteriorated quickly as the company failed to fulfill their promises. “Garcia would call HR, and he's just like, ‘I don't know, man. They said, they're just waiting on HR and I don't know what's going on.’,” J.D. says. “On January 19th, I called him and I said, ‘look...I can't wait anymore. I really appreciate the opportunity, man. But there's these gigs that I’m going to take and I need to make some money. So just let them know that I'm good. You know, I'm not gonna, I'm not gonna try to be a part of your team and the things for the opportunities. And he's like, ‘yeah, man,’ you know, and ‘keep in touch with me’ and ‘blah, blah, blah’.”

In a January 2021 email, WKRG welcomed J.D. to the team.

On January 20th, at 7:30 AM, things got even worse. “The FBI arrested me at 7:30 in the morning, knocking on my front door, coming in guns at the ready, rifles at the ready,” J.D. explains, “Our entire fucking house was surrounded, like I was some type of actual domestic terrorist, planning to kill somebody.”Cuffed and humiliated in front of his family and neighbors, insult was added to injury as federal agents took him into custody. “As I'm walking outside, you’ve got WKRG, the only vehicle out there for the news across the street,” he says.“Mind you, I don't see any cameraman. I don't see nothing. I just see that WKRG vehicle, and I’m thinking, ‘this is fucking great’.” J.D. was taken to an FBI field office for interrogation before being brought before U.S. Magistrate Judge Elizabeth M. Timothy that very afternoon. He was charged with 4 federal misdemeanors and released on his own recognizance.

Over a year and a half later, after a two day bench trial, Jesus Delamore Rivera stands convicted of those crimes. In a 16 page Memorandum Opinion, United States District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly rejected his motion for acquittal, stating that JD was “no mere observer” on January 6th. She went on to explain that his characterizations of various events removed any reasonable doubt she may have had. Even though he committed no acts of violence or destruction that day, Judge Kollar-Kotelli says JD was “a willing and supportive participant in the riot”. In closing, Judge Kollar-Kotelli stated: “He took a side, and it was the side of the insurrection. By his words and conduct, the Court finds Jesus Rivera GUILTY of Counts 1, 2, 3, and 4.”

Many would agree with the Judge’s assessment of JD’s actions that day, while others will decry them as unfair and unjust. Indeed, for every person who declares that JD Rivera did nothing wrong, there are likely just as many who salivate at the thought of seeing him executed as a traitor. This atmosphere of division threatens to destroy the very Union we all claim we are fighting to preserve. Regardless of our differences, all Americans should endeavor to understand what made JD Rivera and millions of others go to Washington, DC on January 6th. Furthermore, we should seek to differentiate between a violent insurrectionist and an impassioned American Chicano with a history of service to the country he loves.

The Rivera Family faces an uncertain future with faith and love.